I have always wanted to be a physician, and through my early experiences, even before medical school, I was particularly drawn to the cardiovascular specialty. I found cardiovascular physiology and the cutting-edge tools fascinating. Ultimately, I chose interventional cardiology as a career path because I felt I could make the greatest impact on patients with cardiovascular disease. It’s been a deeply challenging yet gratifying pursuit.

After more than twenty years of practice, teaching, and research, I’ve been thinking about the people who’ve helped me get here and how I can apply my unique experience to help others and advance the field, especially for women.

From my perspective, the ongoing obstacles to women choosing careers in the cath lab are interrelated, forming a constellation of factors:

- There is a long-standing relatively high percentage of male interventional cardiologists (95%) and, therefore, a shortage of female role models and mentors.

- A rigorous training program that occurs late in training is associated with an unpredictable schedule. This can prove challenging for women who have or are planning on having a family—the physical toll of wearing heavy lead radiation-shielding garments and resulting orthopedic concerns.

- Fears of radiation exposure from fluoroscopy use in the catheterization lab, especially among women planning to start a family.

Each of these factors can affect the others, but collectively, they can dissuade women from entering the field of interventional cardiology. Removing these obstacles can boost female recruitment and increase radiation safety for everyone.

The numerical disparity between the number of men and women cardiologists persists. However, this doesn’t have to be the norm. It has improved in recent years and requires ongoing raising awareness, consistent education, and proactive outreach to continue improving. Practical support for both men and women who work in a cath lab and wish to have families and protect their health is critically important.

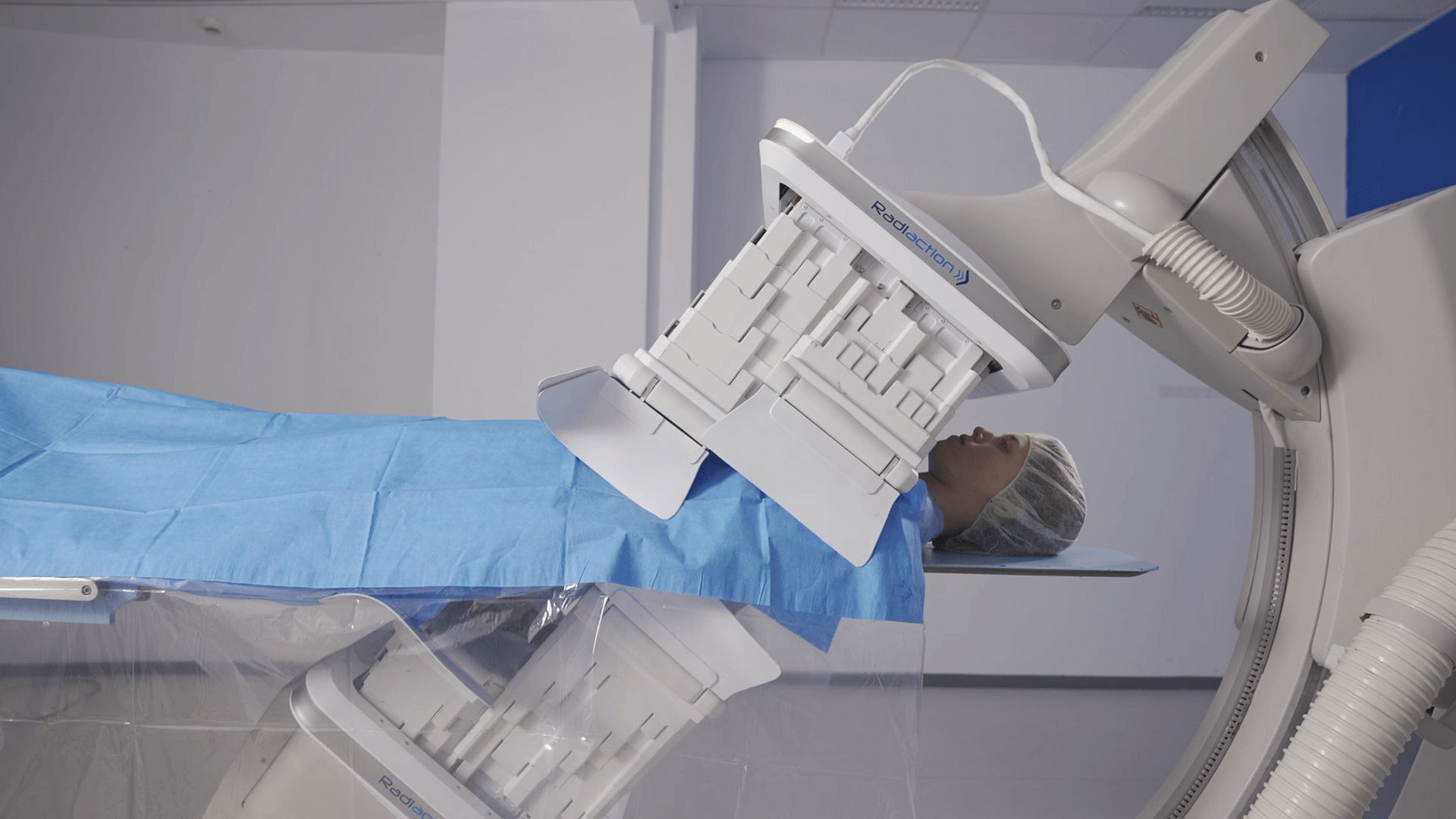

Emergency medical care is inevitably unpredictable, but reducing the weight of radiation-shielding garments is within our grasp. Traditional lead aprons can weigh up to 25 lbs. in some cases, and long periods of wear day-in and day-out can cause severe orthopedic injuries that can force early retirement on otherwise healthy interventionists at the top of their game. Fortunately, new technologies like Radiaction are coming to the rescue. By blocking radiation at the source, the device protects everyone in the room and may allow that 25-pound lead apron to be replaced by one that’s 75% lighter. That alone could prevent extensive orthopedic injuries that are so prevalent among our peers.

Of course, the toughest problem to address is the fear of scatter radiation itself — a main reason women medical students cite as why they choose other careers in medicine. It’s a special concern for individuals who may be planning to become pregnant at some point in their career, and developing fetuses are considered particularly vulnerable to scatter radiation effects. I had my children before starting in the field, so I didn’t face this fear directly. However, I know women who did not choose to pursue interventional cardiology because of their concerns about radiation exposure and how the career choice would impact their families.

The modern scientific truth is that even though wearable lead is inconvenient, tiring, and an incomplete safeguard against scatter radiation, it does a satisfactory job of protecting a fetus in utero. I have several colleagues who’ve gone through pregnancies and child-rearing while practicing in cath labs, and none have reported any ill effects for them or their children. The importance of getting this message out to women medical students and young doctors cannot be emphasized enough and should be spoken about more.

Though the problems I’ve listed are serious, progress toward solutions is already underway. A report published in JAMA Cardiology earlier this year by Sarah Snow and colleagues reported that the number of women in cardiovascular medicine training rose from 18% in 2008 to almost 26% in 2022. In interventional cardiology, the percentage of women in training rose from 6% in 2008 to 20% in 2022. More open and honest communication about radiation safety between doctors, staff, and administrators is occurring, though more work is needed to raise awareness and do the right thing for our cath lab staff and ourselves.

With ongoing, increasing support for change among administrators and cath lab staff alike, we can expect new technological approaches to help reduce the weight of worn radiation protection, which will, in turn, reduce orthopedic injuries. They’ll also raise the level of protection overall, reducing doctor and staff injuries and anxiety about exposures, especially for pregnant people in the cath lab. Along with additional support services (time off, emergency childcare, etc.), these factors can help break down the resistance among women to pursuing careers in cardiovascular medicine. Of course, we must continue to advocate for ourselves and each other, driving reforms whenever progress flags.

Above all else, we need to keep reassuring women that following routine cath lab safety procedures will not result in any additional, untoward radiation effects on fetuses while pregnant. The more institutions and individuals can reinforce this message, the more women we will likely be able to recruit to the cardiovascular medicine team.

This essay is dedicated to the women mentors and role models who’ve guided my career in interventional cardiology: Claire Duvernoy, Dawn Abbott, Roxana Mehran, Cindy Grines, Suzanne Baron, and Alexandra Lansky.

Nadia Sutton, MD, MPH, is an Assistant Professor and Director of Interventional Cardiology Research in the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine within the Department of Medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. As an interventional cardiologist, she is passionate about the clinical care of older patients and focuses on understanding vascular aging and promoting vascular health.